“Welcome to the Machine:” Has the metaphor also evolved since Freedom Summer?

Moving from bottom left corner 1960s, counterclockwise to today:

Thermal fogger, ULV fogger, Helicopter fogging, Drone fogging

Fog machines are a relic from my childhood in the sixties—a memory as unrelenting as the heat and humidity of summer in Mississippi.

Around supper time, as the sun began to slide down the horizon like a riff, aging pickup trucks would emerge like mosquitoes. Soon, the aerosol generators bolted to their beds began to burn oil, forty to eighty gallons an hour, and belch insecticide fog.

The cloud was thick and white, like the cumulus formations that skidded across the sky during the day under our watchful eyes from our positions flat on our backs on the grass. But the cloud from the fog machine was within our grasp. We had only to chase it to find ourselves inside.

And so, children were excused from the table, released into the approaching night. We ran then, down the street behind the machine, as if it carried our very dreams and hopes.

Unaware of the danger.

—Prologue, The FOG MACHINE—

Imagine my surprise when I recently read a post on the NextDoor app alerting Twin Citians that the Metropolitan Mosquito Control District (MMCD)—which serves the seven-county metro area of Minnesota where I now live—has begun mosquito control activity and we can expect to see DRONES, as well as helicopters and trucks, spraying this spring!

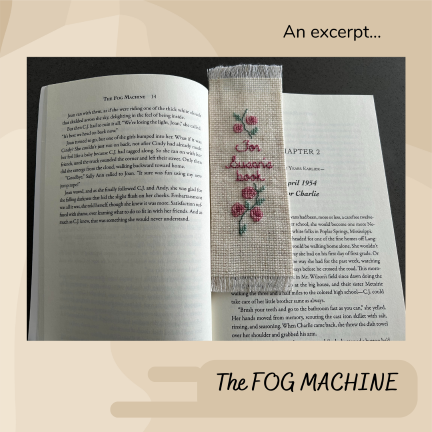

The fog machine serves as a metaphor in my Freedom Summer-centric historical novel The FOG MACHINE. It’s a compound metaphor. Not just “fog”—confusing, mysterious, obstructive. Not simply a “machine”—rhythmic, controlled, organized. But a “fog machine”—poisonous, seductive, pervasive, deadly, distorting, relentless.

Of course, fogging is meant, according to the MMCD, to “promote health and wellbeing by protecting the public from disease and annoyance…in an environmentally sensitive manner.” They “only control the species that bite humans or spread disease.”

The Mosquito Life Cycle

https://mmcd.org/mosquito-facts/

Both the methods of dispersal and the chemicals being dispersed have changed dramatically in the history of fogging. Not just in Minnesota, but also in Mississippi.

As this Mississippi State University Extension Service article explains, “Instead of just routinely spraying pesticides out of trucks several nights weekly, mosquito control personnel are now trying to get the most control with the least amount of pesticides. This involves source reduction to eliminate mosquito breeding areas, larviciding areas of standing water to kill the larvae, and carefully timed, strategically placed insecticides aimed at the adult mosquitoes.”

Why, then, do I use adjectives like “confusing,” “controlled, organized,” “seductive,” “deadly, distorting, relentless?”

What were those old-time fog machines?

Let’s take a quick look back at the fog machines from my childhood. Truck-mounted thermal aerosol generators that produced a highly visible insecticide fog that moved across open spaces, killing mosquitoes in flight.

Here’s what I learned way back in December 2007 from an interview with Robert Ward, retired Manager, Polk County Mosquito Control, Bartow, Florida.

Q: Approximately when were thermal foggers used in the U.S.?

A: The thermal fogger was the sprayer of choice in the early 1960s.

Q: What did the thermal foggers look like?

A: Pickup trucks were used – a cab and chassis. The sprayer was mounted on a plate and bolted on the cab and chassis. The nozzle mechanism cost $500, which was very expensive back then.

Q: Where were the thermal foggers used?

A: Throughout the U.S. but concentrated in California and Florida and along the Gulf Coast.

Q: How frequently, and during what parts of the year, was spraying typically done?

A: This varied regionally, but in Florida it was from April to October and once per week on average. In the 1960s, when there were encephalitis outbreaks, an area might be sprayed several days in a row. Many programs sprayed all night. Others sprayed for the first 2-3 hours of darkness and the last 2-3 hours before daylight.

Q: What prompted the switch from thermal to ULV foggers?

A: A prime impetus for the switch was the fuel crunch of the 1970’s. ULV did not require oil, whereas the thermal foggers used 40 or 80 gallons/hour.

The thermal foggers were also dangerous.

The burn unit fired off gasoline with a sparkplug. A 16-horsepower engine turned the blower and pump. The thermal fog nozzle was nearly “superheated”—cherry red when not spraying.

Occasionally the thermal foggers threw fireballs. This could happen any time during the night of spraying, not just at startup. (Think kids chasing the trucks.)

The fog was so dense that the front end of the vehicle would disappear. And the oily pesticide spray smeared windshields. Both things contributed to accidents. One of the most famous involved actress Jane Mansfield and her children, including three-year-old daughter Mariska Hargitay.

1950s studio portrait of Jayne Mansfield

Credit: Bettmann/Getty Images

What, exactly, were those thermal foggers spraying?

The non-profit, non-partisan Environmental Working Group (EWG) has dedicated itself since 1993 to making us aware of “outdated legislation, harmful agricultural practices, and industry loopholes that pose a risk to our health and the health of our environment.”

An October 11, 2007, EWG “News and Insights” post begins:

IMAGINE a group of gregarious nine- and ten-year-old girls in the early 1960s, laughing and running through the streets of their neighborhood on a summer evening, following along behind a big truck—a big truck spraying the pesticide DDT.

The post continues: “DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane) was synthesized in 1875, but its powers as a pesticide were discovered by a Swiss scientist (who patented his discovery and won a Nobel Prize for it as well) in the late 1930s. It was widely used during the second World War to combat insect-borne diseases, and in the 1950s and '60s it was sprayed widely through many American towns as pest control.”

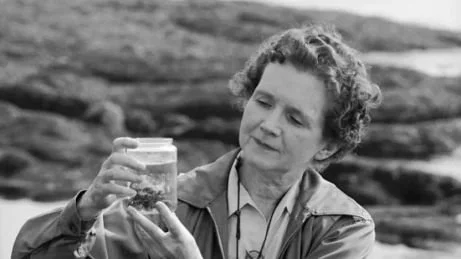

Rachel Carson established a link between DDT and declining bird populations in her 1962 book Silent Spring. As explained in “The Story of Silent Spring” (August 13, 2015), the book: “…meticulously described how DDT entered the food chain and accumulated in the fatty tissues of animals, including human beings, and caused cancer and genetic damage.”

Rachel Carson on a beach in Maryland

Credit: Alfred Eisenstaedt/LIFE Picture Collection via Shutterstock

The “News and Insights” post continues its imagining:

NOW IMAGINE those same girls as grown women, 30 years later, when many of them are fighting breast cancer, and some of them have already lost that fight.

Then adds: “…new research focusing on women's age of exposure found that those who were exposed to the pesticide in the years before puberty had their risk factor increase fivefold. It appears that, given the opportunity to enter the body before breast development, DDT goes to work on breast tissue.”

In 1972, the recently established US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—building on regulatory actions by the US Department of Agriculture—issued a cancellation order for DDT, citing potential human health risks and adverse environmental effects.

Has the Fog Machine metaphor changed, or just the technology?

In The FOG MACHINE, I use the imagery of the fog machine and its seductive pull to represent prejudice as something deeply embedded in all of us and institutionalized in our world: What are we willing to do to belong, to fit in? How do we rationalize our behavior? What consequences do our choices have for others?

The ubiquitous nature of prejudice, as a fog machine, represents a shared human challenge. Not a “Mississippi thing” or “southern problem.” Rather, a learned behavior that can be unlearned, a system that pervades the very pores of society but can be changed.

In this excerpt from The FOG MACHINE, Joan and her friends feel the pull of the fog machine even as Joan struggles with how she is treating C.J., her family’s Black maid, in order to be accepted by her friends.

Joan and Cindy swung the rope low, back and forth, while they chanted, “I like coffee. I like tea. I like the boys, and the boys like me.” When Sally Ann ran in, they began looping the rope and repeating, “Yes. No. Maybe so . . .” They finally tripped Sally Ann up on a yes.

“Ooh, my fortune is good. The boys like me.” Sally Ann clapped her hands.

“My turn,” Cindy said. The rope circled just three times before Cindy stumbled on a yes. “Me, too. I knew it,” she congratulated herself, hopping up and down and twirling in circles. When she stopped, she was facing C.J. standing in the street with Andy. “What’s the matter, Joan? Can’t go outside without your girl tagging along?”

Joan felt what little she’d eaten of supper beginning to rise and she swallowed hard. As she handed her end of the rope to Cindy, she said, “You know how they are.”

While her friends turned the rope, Joan jumped and jumped, not noticing the fog that crept up the street, overpowering the sweetness of the azaleas in Sally Ann’s yard. Only when Cindy suddenly stopped looping the rope did Joan hear the old truck clanking down the street on its mosquito-control mission. She turned to see the lumbering white pickup with the machine bolted to its bed. The nozzle burned red-hot and belched thick clouds of insecticide.

“It’s the fog machine, y’all. C’mon!” Cindy yelled.

Like mice after a piper, the girls threw down the rope to trail the billowy stream. They chased it, fading in and out of view whenever a slight breeze took the fog in unexpected directions.

Joan ran with them, as if she were riding one of the thick white clouds that skidded across the sky, delighting in the feel of being inside.

But then C.J. had to ruin it all. “We’re losing the light, Joan,” she called. “It’s best we head on back now.”

Joan turned to go, but one of the girls bumped into her. What if it was Cindy? She couldn’t just run on back, not after Cindy had already made her feel like a baby because C.J. had tagged along. So she ran on with her friends, until the truck rounded the corner and left their street. Only then did she emerge from the cloud, walking backwards toward home.

“Goodbye,” Sally Ann called to Joan. “It sure was fun using my new jump rope!”

Joan waved, and as she finally followed C.J. and Andy, she was glad for the falling darkness that hid the slight flush on her cheeks. Embarrassment was all it was, she told herself, though she knew it was more. Satisfaction suffused with shame, over learning what to do to fit in with her friends. And as much as C.J. knew, that was something she would never understand.

I assert that the metaphor has not changed. Although fogging technology has evolved to more effectively fight mosquitoes, prejudice and its often-devastating ramifications persist as an ongoing threat to the health of humanity and the environment.

Why is this post linked to Pink Floyd’s “Welcome to the Machine?”

Wish You Were Here (9/12/1975)

“Welcome to the Machine”

Welcome my son

Welcome to the machine

In “The Meaning Behind ‘Welcome to the Machine’ by Pink Floyd,” (American Songwriter, February 13, 2024), Jim Beviglia writes:

“Welcome to the Machine,” sound-wise, comes as close to sci-fi as any Pink Floyd track. But lyrically, it describes an all-too-human verity wherein a beautiful dreamer gets corrupted and used by those looking to monetize those dreams.

The American dream is at play within the realm of prejudice, as is our belief that technology will continuously improve our lives.

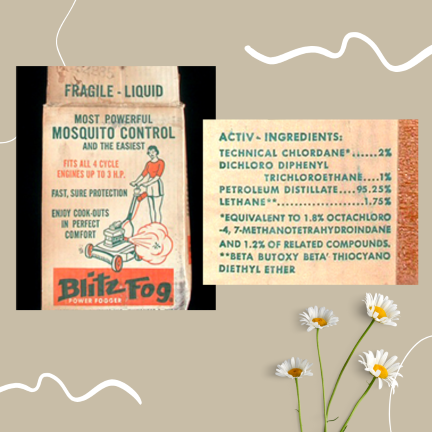

An historical essay (Wisconsin Historical Museum, April 21, 2005 post) on a DDT-based mosquito control product for home use known as “Blitz Fog” chronicles testimony before the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, the first Earth Day founded by Wisconsin Senator and DDT opponent Gaylord Nelson, and the ultimate banning of DDT nationwide.

Blitz Fog, mid-1960s

Source: Wisconsin Historical Museum object #1999.143.22

Astonishingly, the essay concludes with:

Never again will a chemical manufacturer display such a carefree attitude towards chemical poisons as that shown on this package of Blitz Fog, and never again will the public be quite so confident in the unmixed blessings of technology.

Yet nations continue to use DDT to combat malaria. And farmers and home gardeners continue to use pesticides with known health impacts. As concluded in the Environmental Working Group’s October 11, 2007 “News and Insights” post:

Eventually, to combat resistant mosquitoes, nations using DDT to fight malaria will have to transition to another form of pest management. … All that remains is for those funding the spraying of DDT to stop buying into the intentionally confusing messages of the chemical industry and start moving forward with a system that protects against both malaria and cancer. The issue is a lot more complex than the DDT-or-death rhetoric that surrounds it.

Recall my earlier question: Why, then, do I use adjectives like “confusing,” “controlled, organized,” “seductive,” “deadly, distorting, relentless?”

The fog machine metaphor, whether applied to prejudice or racism, is alive and thriving. With ramifications from Jim Crow-era segregation, to barriers to home ownership and wealth accumulation, to policing practices, to the multitude of civil rights under assault today.

As writer and speaker Ijeoma Oluo, whose work on race has been featured in The Guardian, The New York Times, and The Washington Post and whose So You Want to Talk About Race is a #1 New York Times bestseller, has said:

Systemic racism is a machine that runs whether we pull the levers or not, and by just letting it be, we are responsible for what it produces. We have to actually dismantle the machine if we want to make change.