“Kodachrome:” How important is being able to see things differently, especially right now?

For as long as I can remember, I have never liked tulips. I’ve carried an image of them from my fourth-grade geography textbook. Little soldiers bedecking fields in Holland, backdropped by a windmill. Prim and proper. Standing at attention. Most often clothed in the color orange, also not one of my favorites.

Photo by Aryan R on Unsplash

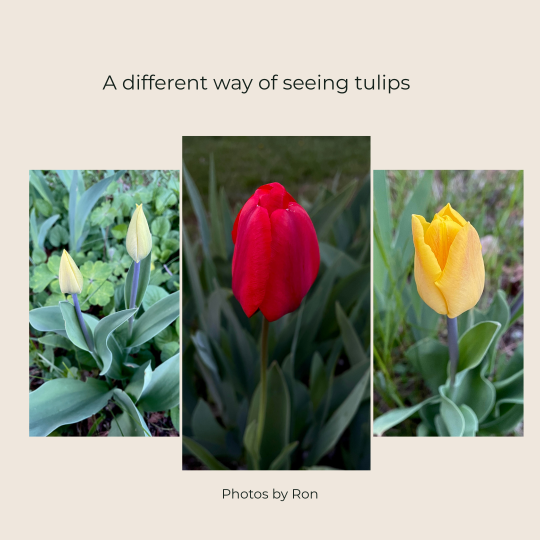

But then one day not too long ago, my friend Ron texted me these photos of tulips from his Idaho garden.

As is our habit, we then engaged in discussion.

Susan: Thank you, Tiny Tim. I’m not a tulips fan but these are truly the loveliest I’ve ever seen. Vivid colors and less “prissy” than the run-of-the-mill tulip.

Ron: Partially because they have closed up for the evening, I think.

Susan: Ah…prime tulip viewing time then!

Ron: The stems are amazing, and the leaves. Are y’all hanging in there?

Susan: I thought the same about the stems and leaves. As vibrant as the flowers! We’re struggling with the world and what we can do to help…

Susan: …Thanks for the exchange about tulips. I’ve started letter writing to my great niece and nephew. During yoga I got the idea to write about perspective. How I’ve always deeply disliked tulips until you helped me see them differently.

What happened here?

I quite literally reframed my view of tulips. Ron’s photos allowed me to change the lens through which I considered them. Now I was looking at them as individuals. Able to acknowledge that some tulips come in colors that are pleasing to my eye. That tulips must open and close when I’m not looking at them locked in some photograph. That their leaves and stems can be as beautiful as their flower. Indeed, that I could open myself up to allowing tulips into my life!

In so doing, I attained a new perspective on tulips. No longer warranting instant malignment.

In essence, I arrived at a new perspective by changing my point of view.

And so it is in writing…

It is the writer’s job to choose point(s) of view and perspective so as to influence the reader’s experience with their story.

“What Is Point of View in a Story? 9 Perspectives To Explore:” https://bit.ly/4eXuduH

How many points of view are there?

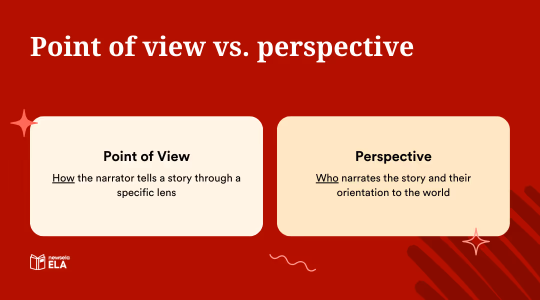

This newsela.com blog post defines point of view as “how the narrator tells the story through a specific lens.”

It’s a little difficult to say how many points of view exist for an author to choose from. First, second, and third-person, of course. But then there are variants. First-person can be central, peripheral, or multiple first. Third-person can be limited, omniscient, limited omniscient, objective, deep (aka close), or alternating third. Then add to those the newer fourth-person, which can be limited or omniscient. But however you slice point of view in writing, you will come up with a finite number.

This New York Film Academy post explains point of view in relation to photography as “the position the camera is in when viewing a scene.” Key photographic viewpoints include eye-level, low angle (worm’s-eye view), high angle (bird’s-eye view) and side angles.

Many other disciplines, such as physics, also make use of point of view. While definitions vary, there is similarity in the importance of choice, be that the author’s, photographer’s, or scientist’s. Just as the lens through which a character tells a story shapes a reader’s reaction, the lens through which people—photographers, physicists, policymakers, or everyday folks—approach a subject affects the outcome.

How many points of view are there then? Some theoretical physicists posit that nothing can exist without being in reference to something else. This leads to multiple definitions of the same reality. So, while the number of points of view in writing and photography is finite, the number of points of view in the world—as in theoretical physics—is limitless.

What about perspective?

That same newsela.com blog post defines perspective as “who is narrating the story and their orientation to the world.”

My historical novel The Fog Machine is told from three perspectives: a twelve-year-old white girl, a young Black woman who leaves Mississippi to work as a live-in domestic in Chicago, and a University of Chicago student who hails from New York and volunteers for Mississippi Freedom Summer. These three characters also practice three different religions. Catholic, Baptist, and Jewish, respectively.

Many disciplines besides writing also make use of perspective. While definitions of perspective vary, there is similarity here too in the importance of choice. And as the author’s orientation to the world shapes the reader’s reaction, so too do the orientations of the photographer, physicist, or policymaker affect the outcome of their work.

How, then, can one’s perspective change?

Is it just a quirk of fate, as with my friend happening to send me very different-looking photos of tulips than the image the word has always conjured up in my mind?

I queried AI on this one. Twice. The two responses vary in a subtle but interesting way.

AI response #1: “Changing one’s perspective requires a combination of self-awareness, openness to new experiences, and a willingness to challenge existing beliefs. It involves actively seeking out different viewpoints, questioning assumptions, and developing empathy for others' perspectives. Ultimately, it's about broadening your understanding of the world and yourself.”

True enough. But stated this way, the emphasis seems to be on self-improvement rather than opening up more opportunities for changing one’s perspective.

AI response #2: “Changing one’s perspective involves actively seeking out new information, experiences, and viewpoints, challenging pre-existing beliefs, and cultivating a growth mindset. It requires being open to different interpretations and recognizing that one's current understanding may be limited. This process can be facilitated by engaging with diverse perspectives, practicing empathy, and reflecting on one's own biases and assumptions.”

I prefer this second response because it’s a proactive stance on what one can choose to do, beginning right away. While we’re working on broadening our understanding of the world and ourselves, we can actively engage with diverse perspectives, practice empathy, and reflect on our biases and assumptions.

Exploring what enables change in human beings is a favorite theme of mine. I’ve concluded this: a complex interaction of family, culture, society, politics, personality, religion, what we value, what we fear, and who we meet determines both our life perspective and our ability to change.

“Kodachrome:” How important is a different way of seeing something?

Thom Donovan wrote in “The Meaning Behind Paul Simon’s Picture-Perfect ‘Kodachrome’” (January 15, 2024): “Looking for a meaning behind the metaphor, ‘Kodachrome’ may be an effort to find the light in a world inching toward darkness and despair. Like film development, it’s a process that sometimes requires much effort. “

Kodachrome

They give us those nice bright colors

Give us the greens of summers

Makes you think all the world’s a sunny day, oh yeah

Donovan adds that, “…though Simon’s classic predates social media by a lifetime, his lyric ‘Makes you think all the world’s a sunny day’ acknowledges how even a ‘70s Nikon in the right hands can frame a narrative.”

I got a Nikon camera

I love to take a photograph

So mama don’t take my Kodachrome away

In today’s tempestuous times, I found the light, or at least a glimmer, when my friend shared those three photographs from his garden.

This small miracle happened because:

We actively engaged with our diverse perspectives, allowing me to learn from him.

I practiced empathy—taking a beat before slamming him for unwittingly sending me photos of my most despised flower.

And I reflected on my own biases and assumptions.

I am so grateful for this experience and the opportunity to change my perspective, even on something as seemingly inconsequential as tulips.

I am grateful that at my age—decades past my formal education—I continue to learn. And that I can share the wonder of that with my young great niece and nephew.

“When you stop learning, you start dying,” said Albert Einstein.

“Learning is not compulsory… Neither is survival,” wrote American economist and management consultant W. Edwards Deming.

“In a time of drastic change, it is the learners who inherit the future,” said American philosopher and social critic Eric Hoffer.